Danny Eisenberg

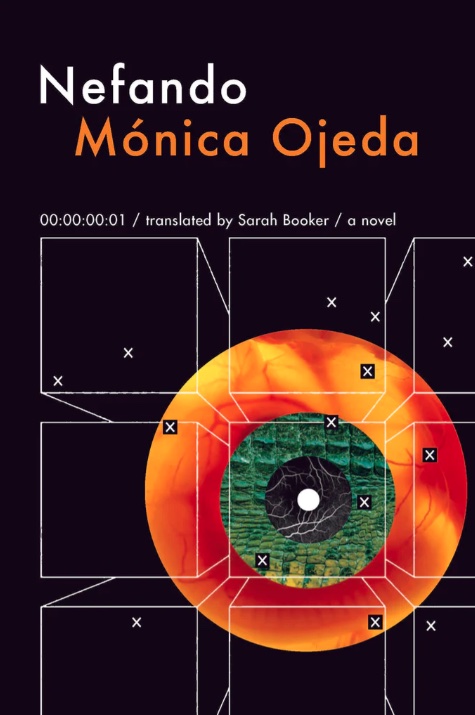

Nefando by Mónica Ojeda

(translated from Spanish by Sarah Booker)

Coffee House Press

164 pages

978-1-56689-689-4

If you think fiction about online subcultures is doomed to quaintness, and that publishing internet discourse in a tangible book inherently renders that discourse obsolete—if, in other words, you believe that our online selves are too ephemeral to capture in something as frozen-in-amber as a novel, then Mónica Ojeda’s Nefando won’t change your mind. It didn’t change mine, at least not in this regard, but Sarah Booker’s new translation has convinced me that Ojeda’s bracing and brazen vision of our tech-addled age is like no other. Folding its virtual realities into a story full of vitriol and viscera, Nefando is a haunting exhibition of all the worst impulses that the internet encourages and enables.

The novel is physical, inescapably so. Scattered throughout its 164 dense pages are episodes and descriptions of sexual violence, animal abuse, pedophilia, public masturbation, pornography, incest, self-castration, and a few old-fashioned beating-the-shit-out-ofs. At every turn a gruesome new deed, a new perversion, dropped matter-of-fact into your lap to make you shut the book in disgust. The book’s title, Spanish for “nefarious” or “unspeakable,” is apt.

As varied as the novel’s transgressions are its forms. One chapter of narrow third-person narration might be followed by a chapter of unsettling second-person, while other chapters constitute a smutty novel-within-the-novel. There are message forum extracts, lines of code, and one chapter consisting only of drawings. Threaded throughout the book are fragments of interviews conducted by an unnamed Ecuadorian journalist (a stand-in, we gather, for Ojeda herself) with three protagonists who speak elliptically about the controversial Deep Web video game that connects them all.

This game, a voyeuristic point-and-click “private odyssey” (and the novel’s namesake), is finally described two-thirds of the way through the book. Next to the precisely rendered horrors of the rest of the novel, the game Nefando sounds, well, like the kind of gaming phenomenon that a writer of literary fiction would dream up. That is, it sounds like a dream as recounted by your friend who has a lot of dreams, going anywhere because its illogic means it can. Fascinating images aside—a woman lies naked on a bed, the player watches and pokes her with the mouse, surreal things happen—the game adds little to the atmosphere of bodily dread that isn’t already contained elsewhere.

Ambitious though Ojeda’s narrative scope and formal experiments are, the experience of reading them is also surprisingly homogeneous. Nefando‘s concerns are largely philosophical, often meditating at length on the meaning and symbolism of an act before proceeding with it. (“The on-screen representation was the most effective proof that the body could become a flat surface in order to project mental imagery, and that what was believed to be nature, immanence, was just an algorithmic construction ready to be innovated,” goes one such train of thought.) Ojeda’s characters, to a one, share this intellectual internal monologue; even from an eight-year-old’s perspective do we encounter the words “autonomous,” “articulable,” and “diaphanous.” Despite a few helpful signifiers—Booker preserves some regionalisms in the dialogue, like the Spanish “tío/tía” and the Mexican “güey”—the characters largely sound the same, created as they are by the same author.

Small price to pay, perhaps, to make an unequivocal distinction between self-indulgence and self-interrogation. Without these lengthy contemplations of characters’ bodies (and of the perceptions of these bodies through sight and screen), Nefando would be guilty of trafficking in the worst kind of shock factor, that of the aimless provocateur. If the laundry list of ordeals is outrageous, then Nefando asks for whose sake our outrage is invoked. Unsatisfied with performances of empathy for the victims of such brutalities as those that populate the pages of her novel, Ojeda counters our instinctual anger with the eerie stillness of an oracle and dares us to object.

“Do you think there are words for this darkness?” demands one character at the novel’s end. The trouble with taboo and disgust is that, more often than not, they leave us speechless, flailing in a pretense of conscience. Ojeda, undertaking the thankless task of putting words to these profound disturbances, has revealed a grim frontier. Not the borderlands of our online dissociations, nor even the extremities of real-world violence, but rather the deepest glimpse yet down the bottomless well of human depravity. The abyss, as always, lies within.

First online publication June 01, 2024

Danny Eisenberg is an MFA student at the University of Virginia and the fiction editor for Meridian #49. He is UVA's 2024 Henfield Prize Winner.